To be a successful investor you need to know two things – How to Value a Business, and How to Think About Market Prices. Buffett wrote about this in his 1996 letter to shareholders.

To invest successfully, you need not understand beta, efficient markets, modern portfolio theory, option pricing or emerging markets. You may, in fact, be better off knowing nothing of these. That, of course, is not the prevailing view at most business schools , whose finance curriculum tends to be dominated by such subjects. In our view, though, investment students need only two well-taught courses— How to Value a Business, and How to Think About Market Prices.

I will be writing several posts focusing on valuing a business and this is the first one. Before learning how to value a business let us invert and learn how not to value a business.

1. How not to value a business

Our ability to process information is limited and we adapt to this limitation by developing heuristics that focus on few pieces of summary information. One such summary information is P/E ratio. Stock price has two components to it. One of them is the actual earnings per share and the other one is the multiple people are willing to pay for $1 of earnings. This multiple is called as P/E ratio and it tells a lot about market expectations for a stock.

But using P/E to value a business is incorrect. Why is that? Price is what you pay and value is what you get. Price and value are not the same and value should be calculated independent of price. One of the component of P/E ratio is price and using that to calculate value creates circular dependency. In the book Accounting for Value Stephen Penman wrote about this.

PRICE IS WHAT YOU PAY, VALUE IS WHAT YOU GET. Unlike the efficient market investor, fundamental investors do not accept price as necessarily equal to value. Price is what the market is asking the buyer to pay, value is what the share is worth. Fundamentalists entertain the notion that prices can “deviate from fundamentals.” So they approach prices skeptically and they challenge prices to understand whether prices are justified by value received. They understand that one buys a business and the business can be a very good business—like Cisco Systems and Dell Computer—but they also know that good businesses can be bad buys—like Cisco and Dell in 1999.

WHEN CALCULATING VALUE TO CHALLENGE PRICE, BEWARE OF USING PRICE IN THE CALCULATION. If one seeks to challenge price, one must refer to information that is independent of price; price is not value, so do not refer to price in calculating value. An investor who estimates a value by applying a P/E (price-earnings ratio) observed in the past or from “comparable” firms is using price to calculate price. Analysts who increase their earnings forecasts because the price has gone up are on a slippery slope if they use those same forecasts in their valuations. And accounting that introduces prices into the financial statements—by marking to market, for example—is in danger of basing value on price. The analyst craves an accounting that is independent of price, an accounting that gives insights about value that can be used to challenge price.

2. A bird in hand is worth two in the bush

If we can’t use P/E ratio to value a business then what should we use? Let us ask the world’s greatest investor on how he thinks about valuation. In his 2000 letter to shareholders Buffett writes

Leaving aside tax factors, the formula we use for evaluating stocks and businesses is identical. Indeed, the formula for valuing all assets that are purchased for financial gain has been unchanged since it was first laid out by a very smart man in about 600 B.C. (though he wasn’t smart enough to know it was 600 B.C.).

The oracle was Aesop and his enduring, though somewhat incomplete, investment insight was “a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.” To flesh out this principle, you must answer only three questions. How certain are you that there are indeed birds in the bush? When will they emerge and how many will there be? What is the risk-free interest rate (which we consider to be the yield on long-term U.S. bonds)? If you can answer these three questions, you will know the maximum value of the bush — and the maximum number of the birds you now possess that should be offered for it. And, of course, don’t literally think birds. Think dollars.

Aesop’s investment axiom, thus expanded and converted into dollars, is immutable. It applies to outlays for farms, oil royalties, bonds, stocks, lottery tickets, and manufacturing plants. And neither the advent of the steam engine, the harnessing of electricity nor the creation of the automobile changed the formula one iota — nor will the Internet. Just insert the correct numbers, and you can rank the attractiveness of all possible uses of capital throughout the universe.

Time value of money states that a dollar in hand today is worth more than a dollar to be received in the future. This is because a dollar today can be invested to earn some return. Let us assume that your friend is asking you to partner with him in a real estate business. After one year the business will fetch you $110. How much would you pay for it today? If you are expecting a 10% return then you will pay $100.

Valuet+1 = Valuet * (1 + rate of return) Valuet = Valuet + 1 / (1 + rate of return) Valuet = $110 / (1 + 0.1) Valuet = $110 / 1.1 Valuet = $100

If you get $110 after two years then you will only pay $90.90.

Valuet+2 = Valuet * (1 + rate of return)2 Valuet = Valuet + 2 / (1 + rate of return)2 Valuet = $110 / (1 + 0.1)2 Valuet = $110 / 1.21 Valuet = $90.90

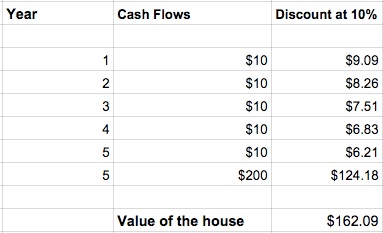

Consider the cash flows produced by a rental property given below. You receive a rent of $10 from the house each year for five years and after that you are planning to sell the house for $200. How much would you pay for the house today if you are expecting a 10% return? You should pay $162.09.

3. Discounted Cash Flows

In the rental property example we used yearly rents and final sale price to arrive at the value of the house. We can apply the same technique for valuing a business. Instead of yearly rents we will use free cash flows and instead of a final sale price we will use continuing value. This technique is called as Discounted Cash Flow (DCF). Let us understand this with a simple example.

Consider the data given below for a business which I made up. Also the company has a long term debt of $100 million and has 10 million shares outstanding. Each share is trading at a price of $230 on 01-Oct-2014. Should you buy the stock?

The company is growing its cash from operations at a decent rate and investing 30% back into the business. The cash that is left over after investing back into the business is called as free cash flow. After discounting this at 10% we get the total present value of free cash flows as $503 million. Looking at the data it is clear that the company will be able to grow its free cash flow beyond 2019. Also a company is a going concern which will generate free cash flows for a very long time into the future after 2019. But how do we value that?

Free cash flow end of 2019 = $200 Free cash flow grow at 5% forever = $200 * 1.05 Free cash flow grow at 5% forever = $210 Continuing value beyond 2019 = Free cash flow / (rate of return - growth rate) Continuing value beyond 2019 = $210 / (1.1 - 1.05) Continuing value beyond 2019 = $4200 million Discount continuing value at 10% = $4200 / (1.1)5 Continuing value after discounting = $2607.86 million

The value beyond our forecast horizon of 2019 is called as continuing value and it comes to $2607.86 million. Most of the steps given above should be clear except the ones marked in red. How did I arrive at a 5% growth rate? It was an educated guess. Why did I divide free cash flow by (rate of return – growth rate)? For generating $210 how much capital do I need? I need $2100 as 10% of $2100 is $210. But why did I subtract growth rate? Remember I assumed that the free cash flow is growing at 5% forever and hence I am bringing down the rate of return by 5% so that I account for continuing growth and this adjustment will result in higher continuing value. It’s time to calculate the enterprise value of the company.

Enterprise value = Present value of free cash flows + Continuing value beyond 2019

Enterprise value = $503 million + $2607.86 million

Enterprise value = $3110.86 million

Enterprise value = Value of equity + Value of Debt

Value of equity = Enterprise value - Value of Debt

Value of equity = $3110.86 - $100 million

Value of equity = $3010.86 million

Total outstanding shares = 10 million

Value of each share = $3010.86 / 10

Value of each share = $301.08

Price of each share = $230

Price to Value = $230 / $301.08

Price to Value = 0.76

The stock appears undervalued as you are buying a $1 for $0.76.

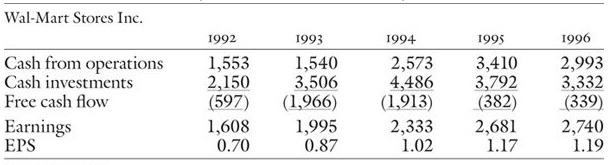

4. Limitations of DCF

Take a look at Walmart’s free cash flow from 1992 to 1996. It’s negative as cash from operations is invested back into the growing business. If you apply DCF then then you will get a negative value. How can Walmart’s value be negative when its EPS during the same period grew by 11.20%? In the book Accounting for Value Stephen Penman explains this beautifully.

The problem with DCF valuation is an accounting problem. Cash flow from operations is the net cash from selling to customers and of course adds to value, but the FCF calculation then subtracts cash investment. This is odd because investments are made to add value, not reduce it (the notorious corporate jet aside). Firms consume cash to generate value (that’s fundamental!). Firms reduce FCF when they increase investments (reducing value in the DCF calculation) and increase FCF when they reduce investments (increasing DCF value). Using FCF in valuation is not only odd, it’s perverse. As firms increase FCF by liquidating investment, FCF is more a liquidation concept than a measure of added value from increasing investments. In short, FCF is not good accounting for value.

In the last section for the fictitious company we came up with an enterprise value of $3110.86 million. Around 84% of this value comes from continuing value. Instead of 5% growth if we assume 3% growth then the enterprise value comes to $2330.27 million and per share value goes down to $223.02 and price to value goes up to 1.03. A small difference in growth rate assumptions can lead to huge differences. This is dangerous and with excel sheet in hand human mind can justify any price it wants.

The concept of future prospects and particularly of continued growth in the future invites the application of formulas out of higher mathematics to establish the present value of the favored issue. But the combination of precise formulas with highly imprecise assumptions can be used to establish, or rather justify, practically any value one wishes, however high, for a really outstanding issue. — Benjamin Graham, The Intelligent Investor

DCF uses cash flow accounting instead of accrual accounting. Cash flow accounting might be OK for a tennis club but not for valuing a business. Penman explains it beautifully.

Accrual accounting has two enhancing properties. First, investments typically are not allowed to affect the value-added measure, earnings. Rather than being “expensed” against cash flow from operations, investments are booked to the balance sheet, to book value. As assets, they are seen as something that produces value in the future rather than as a detriment to value. Second, cash flows from operations are modified by additional “accruals.” Revenue is booked when the firm has a claim on a customer (a receivable), not when cash is received, and expenses are booked when a liability is incurred to suppliers, not when cash is paid. Both bring the future forward in time. So, for example, if a firm remunerates employees with pension benefits to be paid thirty years in the future, a DCF valuation will have to forecast cash flows thirty years hence, in the long run. But accrual accounting includes the value affect as an expense in earnings immediately (and books a corresponding pension liability to the balance sheet). That brings the future forward, reducing our reliance on speculative forecasts of the long term. And it produces a number, book value, which one can potentially anchor on. Accrual accounting even recognizes value when there are no cash flows: If a firm pays employees with a stock option, accrual accounting records wages expense even though there is no cash flow. A DCF valuation misses that.

5. Buffett Owners Earnings

Alright DCF let us down. Let us go back to Buffett for help. We know that he uses owner’s earnings for valuation. You can read about it here and the crux is given below. By using reported earnings he uses accrual accounting instead of cash flow accounting. Also the capital expenditure (capex) he refers to is maintenance capex and not growth capex. Once again he fixes the problem which we had with DCF as growth capex adds value for a good business.

Owner Earnings =

reported earnings plus (A) +

depreciation, depletion, amortization, and certain other non-cash charges (B) -

average annual amount of capitalized expenditures (C)

A + B - C

But how do we know the maintenance capex? If an investor knows the business very well then he might. But it is an elusive concept which requires too much judgment for most of the investors. Should we avoid it then and instead depend on GAAP depreciation? That’s what I would do. Are there any other issues with owners earnings. Yes there is. Certain expenses like Advertising and Research & Development create enduring advantage. It should be kept in the balance sheet and amortized over a period of time. But instead they are expensed immediately in the income statement which reduces reported earnings. I would highly recommend this twitter debate on owners earnings.

We started the post with P/E ratios and ended with owners earnings. Also we learnt about the limitations of DCF. But we are not done yet. In the next post I will introduce you to the residual earnings method.

Hi Jana,

Thanks for the detailed post.

Hi Jana,

Excellent post. I have been wondering how you are able to amass such a wealth of information on a continuous basis that too on multiple subjects. I have been trying to replicate this in my life but most of the time I find myself switching between the subjects and never getting a good grip on a single subject.I am not sure where exactly I start and how do I progress. Is there a guidelines or a good plan to follow. My aim in life is also to master the best of what others have already figured out. Any suggestion would be highly appreciated.

Mohan,

Thanks for your comments.

I am not an expert and still in the process of figuring out how to connect ideas from multiple disciplines.

The only suggestion I have is to read one book at a time and take notes while reading. See how the concepts you are reading relates to other disciplines. Once you are done reading close the book and summarize your understanding in a single page. Use mind maps to deepen your learning.

Keep doing it for each book and over time you will start to see the connections.

Few useful links worth considering

http://www.farnamstreetblog.com/how-to-read-a-book/

http://www.ryanholiday.net/reading-isnt-a-race-how-speed-reading-and-spritz-completly-miss-the-point/

http://betterexplained.com/articles/adept-method/

https://janav.wordpress.com/2014/11/03/mungers-psychology-mindmapped/

Regards,

Jana

Reblogged this on Random thoughts of an Insecure Investor.

Hi Jana,

Thanks for a very insightful post. You have captured the essence in a very concise manner as always.

I had a question pertaining to the treatment of operating leases while calculating Owner’s Earnings. Should we be capitalizing these if it reflects investment in an asset vital to the operations of a business?

e.g. Jet Airways leasing aircrafts from Boeing for a short period but classifying it as operating lease

Rohit,

I thought about it for some time and it’s better to treat the cash paid out for leases as an expense. For an airline business these costs make up a bulk of expense and capitalizing them doesn’t look right to me.

Regards,

Jana

Hi Jana,

I don’t know how to value business and Prof. Bakshi recommended me Value for Accounting. I have just started reading the book and stumbled on your this post. It has helped me understand the concept better. Thanks a lot for this post! 🙂

Thanks Manish.

Regards,

Jana